Narbonne Visigothique!

Visigothic Mysteries of Narbonne

The Cross of Silence in the Town Hall entrance in Narbonne - remarkably similar tothe one found at Rennes-le-Château.

We asked the tourist office in Narbonne for any details of the Visigoths. The girl behind the desk shook her head dolefully. She’d never heard of the Visigoths. So we went to the Lapidaire Museum. This is housed in a church, Our Lady of Lamourgier, that was desecrated at the time of the Revolution and left empty and useless. A hundred years later, the town was taking down its ramparts to build an inner ring-road. The ramparts had been erected in medieval times, on Roman foundations, using the stones from ruined ancient buildings. As the ancient walls were dismantled thousands of these stones, some with inscriptions or carvings, were put in the church for safe keeping, thus forming the largest collection of such stones in Europe. Most were Roman; some were Visigothic or “paleo-chrétien”.

When we asked the lady on the desk which stones were Visigothic she shrugged. She’d never heard of the Visigoths, she told us.

One day we went into an antique dealers in the rue du Ancienne Courrier, bang in the centre of old Narbonne. “Have you got any Visigothic coins for sale?” “No. Go to Toulouse. THE VISIGOTHS NEVER LIVED HERE,” said the dealer.

The Visigoths lived in Narbonne from 462 until they integrated with the Carolingians in 768! The role the Visigoths played in the history of Narbonne for some 300 years is a fascinating and dramatic story, yet few local people believe anything other than school children’s history; they were beaten out of France by Clovis and never lived in Narbonne. A Frankish cover-up?

A beautiful capital

When the Visigoths came to Gaul, Roman Narbonne ruled the area called the Narbonnais, the most prosperous province in all the Roman Empire. The road linking Rome with Spain, the Via Domitia, ran through the centre of the town, with the Horreum beside it, the underground warehouse where goods in transit were stored and markets were held. The Via Domitia crossed the river Axat, later the Aude, and there made a crossroads with the Via Aquitania; westwards ran to Carcassonne and Toulouse, south towards Perpignan, with a branch road off to the Roman port, now La Nautique, on the étang de Bages et Sigean.

Domitius Ahenobarbus had founded a Roman garrison here in 118BC; Narbo Martius made it the first Roman capital of the newly conquered Gaule, hence the name Narbonne. Narbonne became a great cultural centre. The delights of Narbonne included the large and splendid Roman buildings, including the Capitole.

In 414, when King Ataulf and he Roman princess, Gallia Placidia, celebrated their sumptuous wedding, Narbonne was enclosed by stone ramparts, hastily repaired after the threat from the Vandals in 407, not around Narbonne as we know it today, but around the Roman centre, with its Forum and Capitole. The widely spaced Roman villas, the amphitheatre, the basilicas or temples and the graveyards, were outside the walls, most of them in the area to the south of the river called Le Bourg.

“Le Bourg” - yes, it is a northern European word, and this southern part of Narbonne was named this by the Visigoths.

After the brief stay of Ataulf, the Visigoths under Wallia and then Théodoric I established themselves in Aquitaine, but they hadn’t forgotten Narbonne. Narbonne ruled from the Rhône to the Garonne to the Pyrenees, owning all that territory. It was closer than Marseille and it was on the sea; the Visigoths needed their own port. So Théodoric I tried a siege in 436, without success, and then, due to someone else’s quarrels, under Euric they gained Narbonne in 462.

Narbonne under Euric

The local people of Narbonne were nervous in that year 462. They had just lost their much-loved Orthodox bishop, called Rusticus. Rusticus was ordained in Narbonne in 427 and lived until 461. His church, Ste Marie, was built on the site of a Roman house which sheltered Christians during their persecution from Rome in the early 4th century. It was destroyed by fire in the Visigothic siege of 436 and Rusticus rebuilt it. He laid the first stone in October 441 and the building was finished by 29th November 445, paid for by contributions from rich people in Narbonne. An ornamental lintel describing these events is still in the museum in today’s cathedral buildings.

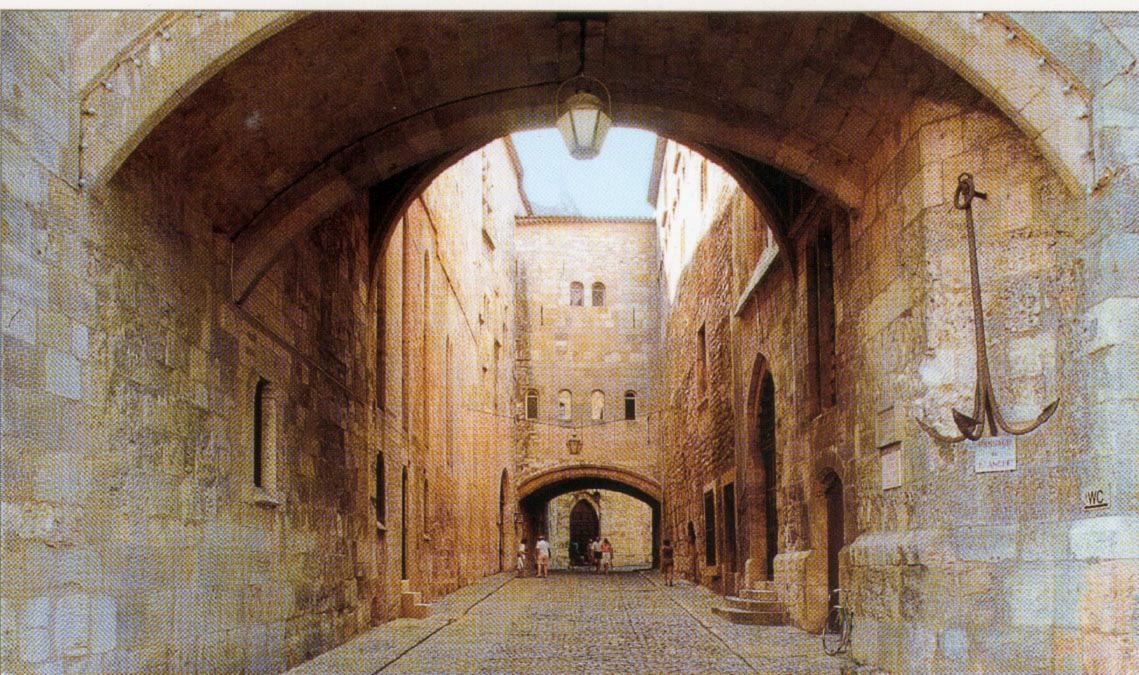

Also in today’s buildings is the Passage d’Ancre, (picture below) used in the 5th century for the soldiers to walk from the square in front of the cathedral and past the cathedral of Rusticus, on their right, to reach the town’s ramparts. The soldiers controlled the passage of fish and other goods (hence the name Ancre) for a fish market was held in the square every day, and the custom lasted nearly 2,000 years until today’s covered market, Les Halles, was built in 1901.

The ramparts were the original Roman ones around old Narbonne, and are still there, although renovated, today. When the building of today’s cathedral began on 3rd April 1272 there was talk of removing the ramparts to make the cathedral even bigger; but in 1355, the Black Prince arrived and burnt Le Bourg. Valiant defence organised by the viscount Aymeric VI saved “the city” and the walls remained.

Rusticus was admired as a preacher by the local people. They followed his debates with great interest, these were on themes such as “Should priests who had committed great sins be forced to do penance in public?” Tricky!

Near his new cathedral Rusticus built a church to the Virgin and also, outside the ramparts, a basilica in 456 to St. Felix, who was martyred at Gerona. Rusticus was sincerely mourned when he died after 34 years service. He was buried in a chapel near what was then the River Aude, and his deacon, Hermès, placed a stone saying; “Pray for me, who is your dear Rusticus.”

When the Visigoths arrived, the people were afraid they might be forcibly converted to Arianism. The Auvergne bishop, Sidoine Apollinaire, who resisted Euric for a long time, did not want the “domination of their race or their sect.” The Catholic bishops seemed to think violence would be used - after all, that was the rod Catholics used when they wanted to convert somebody.

But the Visigoths loved Narbonne and admired the Roman way of life. In the event, the churches were not persecuted and they began to flourish. Hermès became the next bishop. In 463 the Visigoths repaired the town walls and the people began to feel life might not be so bad after all. I read in a French history book; “The Visigoths, the least bad of the barbarians, are remembered for preserving the Roman way of life. They contributed to Narbonne a certain sparkle and a powerful church.”

When Sidoine Apollinaire visited in 465, 3 years later, he wrote a eulogy to Narbonne; “Rich and healthy, beautiful to see your town and your countryside at this time, with walls, citizens, your shops, your gates, your forum, your theatre, your sanctuaries, your financial exchanges, your hot springs, your arches, your attics, your markets, your fields, your fountains, your islands, your salt marshes, your étangs, your river, your goods for sale, your bridge, your coast. You are the only one with a just title to venerate the Gods Bacchus and Cérès, Palès and Minerve, graced by your spears of corn, your vines, your pastures, your olive presses.” Was he writing tongue-in-cheek again? Attics indeed! We note he never quoted Christian gods.

A local aristocracy grew up, as many Roman poets and lawyers came to live in Narbonne. One was Consentius, who trained many “legal eagles” in his school, all recruited from the aristocracy. He was a typical Roman nobleman of the day. He had worked in the office of the emperor Valentinius III in Rome in 440. He became a magistrate and was useful in negotiations with Constantinople, for he spoke Greek. In 456 he was made a count under Avitus and then retired to Narbonne, the “swan of the Aude,” where he became a senior adviser to King Euric.

The Roman nobility lived in opulent villas, several of which are known today. The one owned by Consentius was called Octaviana. Among the fields, vineyards and olive groves, the beautiful villa was ornamented with fine art, grand gateways, springs, baths and a little chapel. It’s there that Sidoine Apollinaire used the library and socialised with the masters, playing ball games, or enjoying sophisticated conversation at the dinner table. The villa was near Ormaisons and is sometimes called Hautrive.

The Mystery of Hautrive

Many villas near Narbonne in the Corbières, “Hautrive near Ornaisons and Villamajou near Gasparets”, were burnt to the ground. Hautrive near Ornaisons was “destroyed during the Germanic invasions.” As it is generally assumed the barbarian invasions were in 407, how come Sidoine Appolliaire was describing his days at Hautrive in glowing terms - in the years 471 to 473?

Georges Labouysse says of the Toulouse villa Montmaurin, owned by a nobleman from Toulouse and burnt by the Vandals; “it was never rebuilt by the Visigoths, like many others such as Hautrive near Ornaisons.”

Hautrive, then known as Octaviana, was given to the nobleman Consentius around 463 by king Euric. Had it been re-built by the Visigoths? That seems unlikely. I think it was never destroyed in the first place.

Was it then ransacked by either the Burgundians in the 6th century - 585 or the Francs in the 8th - 737? It’s quite likely Gontran passed his way in 585, when he was attacking Septimania, but surely he would not have destroyed the villa if Romans, the descendants of Consentius, were living there, but only if it was occupied by his “horrible” Goths.

But Charles Martel in 737, after he failed to take Narbonne, laid the entire Narbonnais to waste before he returned to his French kingdom. It’s likely he burnt Hautrive and killed or took prisoner any workers who could not escape in time. So when local history books tell us Hautrive was destroyed by the barbarians, they are more correct than they know; it was destroyed by the Franks in 737.

Where exactly is Hautrive?

Octaviana - now a wine château

Looking for it we passed signs for a wine château called Octaviana and then found Hautrive-le-Haut and Hautrive-le-Bas to the south of Ornasions, but residents walking their dog along the road had never heard of any Roman villa at either place. Then, 2 kilometres to the south of Gasparets, we found Villemajou, now a private farm and winery. As the name means “grand villa” could this have been the place? Yes.

The “villa” was in reality a grand domain of some 8 square kilometres, roughly square shaped and stretching from Fonte-Sainte in the west to the river Aussau in the east, then north to the two Hautrives and Prat-de-Bosc. Villemajou was the main house; from its hill looking east was the plain of Gaussan, a lake at the time, while in the other direction, the baths fed by Fontsainte and the well at Saint Siméon could be seen.

Here were found two beautifully decorated pools, with arcades around and marble columns. Between the main house and the pools were gardens, fields, vines and olive groves. The description tallies well with that of Sidoine Appollinaire, who wrote lyrically of his happy days spent at the villa of his friend Consentius. Archeologists have discovered marble pillars and capitals, detailed brickwork, mosiacs, lamps, belt buckles, jewellery, Roman coins and the remains of two Roman roads. Near La Bousquet, just west of today’s Boutenac, were the remains of an amphore workshop with ovens similar to those found at Amphoralis near Sallèles d’Aude.

The farms and workers’ houses of Octaviana later grew into the domains called Hautrive scattering the district today.

The churches and religions of old Narbonne

In 462, when Euric arrived, were seven churches, including one to Ste Marie, one to St. Felix and one to St. Marcel. Ste. Marie was today’s cathedral, and St. Felix was opposite where is today the railway station. Marcel and Cassien were martyrs of Tangier at the end of the 3rd century. Their church, built in the 5th century, was one of the first to use a crucifix as a symbol, for the altar base, carved with such a cross and an inscription, is in the museum of today’s cathedral.

Outside the city walls were the basilicas, dedicated to the dead, rather than the living. They had relics of martyrs from far away, and they had graveyards. The most important was St. Paul Serge and had an extensive graveyard, stretching as far as the River Axat (which is now the Canal du Midi.) It could have been where Rusticus was buried. The Visigoths, like the rest of the populace, buried their dead in this graveyard when they lived in Narbonne.

Part of the graveyard is just to the north of today’s St. Paul’s church. You can also visit it inside the church. It is called the “Crypte paléo-chrétienne” and is kept locked, but the verger will come with his key and take you in. Entrance is free, as it is to the church itself. You can see the old mosaics and various stone coffins. The Roman ones are decorated with figures, faces, gods and goddesses, the Visigothic ones with natural forms.

At St. Paul’s a medallion was found similar to those found in Aquitaine at the end of the 5th century. The typically Visigothic medallion had a picture of Christ and the letters alpha and omega, and implies a love of St. John’s gospel (later much beloved by the Cathars.) “In the beginning was the word . .” They also had a love of the book of Revelations. Chapter 22, verse 13 says; “I am alpha and omega, the beginning and the end, the first and the last.”

The church of St. Paul Serge was built in the place “where the evangelists preached” (but also over the grave of St. Paul Serge), around 250AD. These men preached Arian christianity; the Trinity had not yet been devised by Constantine.

But by 462 it was the Roman Church that prevailed in Narbonne. Sidoine and Rusticus had opposed the Visigoths for their Arianism, but Rusticus died and Sidoine Apollinaire was exiled, although he was allowed back to Narbonne later due to the influence of Léon. The Visigoths under Euric were neither fanatical nor consumed with conversion zeal. They just wanted a peaceful life.

At the time, the Roman Church was over-sensitive. The Arian Church to which the Visigoths belonged, the Coptic (Egyptian) church and the Celtic Church were all bigger than the Catholic church; and none of them believed in the Trinity. Neither did the Jews and the Muslims. Hard to believe now, that the Roman church was fighting for its life at the time. They fought hard, using all the means at their disposal, which included the Roman army, and became powerful enough to destroy all documents which exposed the history they proclaimed as - well - not quite true.

The Arian Visigoths were considered heretics, but they “honoured the churches and graveyards.” Maybe at the time, the Visigoths considered themselves benign and tolerant of the upstart Roman church.

The condemnation of Visigoths for their religion is still being made today by the Catholics of France - while all the time the Visigoths were much more tolerant than the Roman Catholic church ever was. “The sense of right which lived in the Visigothic kings made them better able to accept the existence of the Catholic church” says The History of Narbonne.

Inscrivez-vous au site

Soyez prévenu par email des prochaines mises à jour

Rejoignez les 21 autres membres